Two Books

Read at Story Salon, 6 December, 2006

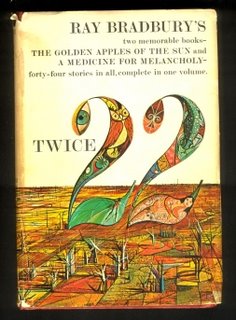

I have two books with me tonight. Both by Ray Bradbury. One is among the first hard-cover books I ever owned, a collection of his short stories. I got it when I joined the Doubleday Science Fiction Book Club. It was in my room when I was in in high school, it went to college with me, it has been in several apartments and two houses. I always know where this book is.

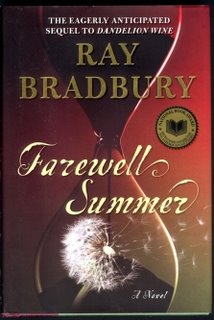

The other is a copy of Farewell Summer, freshly published. Bradbury claims to have been working on it for about fifty years. It’s the sequel to Dandelion Wine but not really, it’s more like a continuation of the other book, an echo. A grace note.

This book is autographed. Mr. Bradbury signed it for me at a book store in Glendale a couple of weeks ago. He turned eighty-six this past August and the man who promised his friend he would grow old but never grow up, is diminished. He arrived at the shop in a wheelchair. He signed his name carefully. He has the hands of an old man, but not the eyes.

He signed this book and another copy of Dandelion Wine and I thanked him. I thanked him.

Bradbury’s one of the troublemakers from my youth. One of the writers who got in early, before I knew what they were really up to. They got in the blood and they’ve never left me. The older I get, the more I write, the clearer I see them threading through me and I’m grateful for the company.

You read Bradbury as a boy and then you go back to him as an adult and you know they’re the same books, the same words, but somehow they’re completely different. You’ve grown into them somehow and what you liked for the magic and the wonder as a kid, you cling to for the melancholy and the depth as a grown-up. The first reading leads to the second reading. Without the first, the second reading lacks resonance.

Bradbury is the great authorizer, especially of boys and the men they become. Men that contain the boys. He once told a friend of mine who was contemplating a big life change, “Jump off the cliff and grow your wings on the way down.” Suicidal as advice, but golden as a metaphor. Advice you can get from anybody, but a good metaphor, that’s rare.

Bradbury was also a way into a denser language. He was willing to pile metaphor on top of simile on top of reference, like a juggler piling chairs. Some of the constructs are awkward, but you’re impressed how high he can stack. He once wrote, “It was a fog inside of a mist inside of a darkness.” I don’t know what the hell that means, but you encounter a sentence like that, you know you can lean on it in a high wind. “A fog inside of a mist inside of a darkness.” You have to be pretty damn fearless to try a sentence like that.

Like most timeless things Bradbury is out of fashion at the moment, replaced by the current hot style in writing, which is illiteracy laced with plagiarism.

There’s a story in this book, written in 1956, about a man walking along a beach in Biarritz at sunset and seeing a man on his hands and knees drawing in the wet sand with an ice-cream stick. Remarkable stuff this guy’s carving into the beach, beautiful. The man gets close to the beach bum doing the drawing and that’s when the artist looks up and the man realizes it’s Picasso. Picasso doodling in the sand with an ice cream stick. A unique work of art and he’s the only one there. He thinks about running for a camera, but the sun’s almost gone. So, he walks back and forth, trying to remember everything drawn in the sand. The story ends with him having dinner back at his beach front hotel, listening to the tide coming in.

These are the stories that whack you as an adolescent, long before you really know what they mean. You know you’re reading the real stuff. And you struggle to retain it, even though the tides going to come in eventually.

So Bradbury wrote in my book. He signed his name not with an ice cream stick, but with a Sharpie. And somewhere there’s the sound of waves on sand.

There are forty-years between these two books. In one hand, I can hold myself as a kid and a grown-up and you can’t see any light between them. What do you suppose that means?

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home